Kota in Rajasthan is famous for its coaching centres and now infamous for student suicides. Fourteen students have died by suicide in the first six months of this year. How does the coaching-hostel system function and what is it like to be a student in Kota.

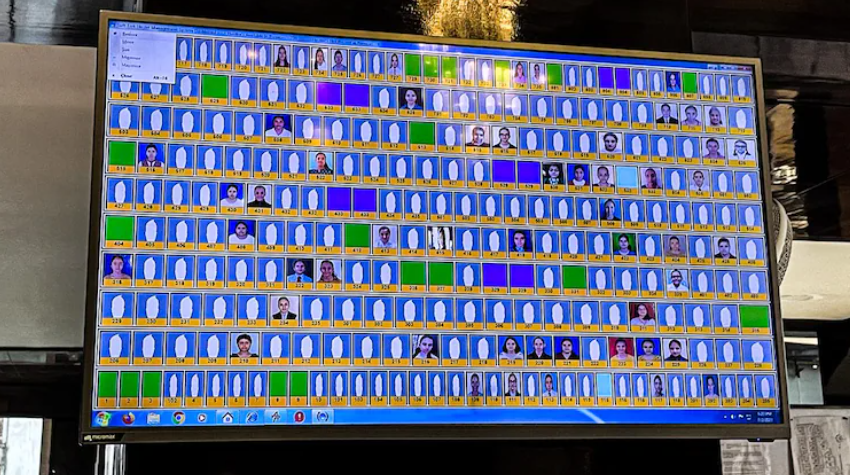

With a huge reception hall, grand chandeliers and luxurious furniture, this hostel in Kota looks fancier than even a five-star hotel. The owner takes me around and shows all the arrangements — CCTV cameras, biometric systems and nets laid out in every corner of the building. “Even if children try to jump to their death, they will get caught,” he says with pride.

Kota is not just about big hostels or institutes, it’s about big dreams – the dream of acing NEET or JEE and becoming a doctor or an engineer.

Coaching institutes run with the promise of fulfilling these dreams. A whole business system feeds them and thrives on them.

They turn a 15-16-year-old child into a living machine. Everything goes on smoothly, until a machine stops working.

In the last two months, nine children have died by suicide.

One student jumped off a roof. Another hung himself from the ceiling fan. Some wrote suicide notes. Some went quietly. The room remained closed for some days. Then, after it was washed, it was allotted to another student. Everyone, it seems, is working together to remove the scent of death.

“Kota sits on a pile of gunpowder,” a senior police officer says on condition of anonymity. “One spark and all the glitter will be reduced to ashes. Buildings will turn into boxes. This city is living at the cost of a dead childhood,” the officer adds.

ENTIRE KOTA FEEDS THE SYSTEM

When I started for Kota, about 500 kilometres from Delhi, I had done some homework. There were some numbers on which calls had to be made. There were some people with whom I had to meet.

But as soon as I came out of the railway station, the homework I had done was of no use. I became a character in my story.

the moment I stepped out of the station, auto drivers swarmed me — some assuring me that they would get me the “best hostel in Kota for my child”. Some others were promising me a seat in a top coaching centre at a cheaper price. I was taken for a prospective client.

Marketing for the coaching system starts at the railway station itself.

I take a cab, still in the garb of a customer.

The driver is a man of few words. After I initiate a conversation, he says, “Ma’am, bring your child to this city only if you can leave behind everything and stay with the kid. This city bears the curse of many innocent hearts.”

The driver’s face was emotionless and his eyes were lost.

I didn’t meet the driver again, but for the next one-and-a-half days, I found the same lost look everywhere in Kota. Children mumbling among themselves at a sugarcane juice cart. Students peering into books unmindful of the tea going cold in the cups nearby. Children in the common area of a hostel repeating “Sab badiya hai”, as if in a daze, when asked how things were.

The system to turn kids into machines started in the 80s when a student from a coaching institute made it to the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT). The coaching institute became famous overnight. And soon, several coaching institutes mushroomed in Kota.

The tiny stream of students turned into a swollen flood-fuelled river of lakhs of children.

Then hostels sprang up to accommodate them. Canteens opened too. From stalls of tea and snacks to auto-rickshaws, all joined in.

The target was the same for everyone — 15-16-year-old children. The entire city was chasing them with a densely woven net.

IN CONVERSATION WITH AN IIT-ASPIRANT

This year, around 3 lakh students have come to Kota to prepare for entrance exams, say hostel owners and other sources.

As part of our interaction with students, we meet Samar Singh, who is preparing for IIT entrance exam. He landed in Kota two months ago.

Today is Sunday, but there’s no sign of it being a holiday anywhere. “Today the students either make up for the lost sleep or go to coaching centres to take tests,” says Samar.

“When do you wash your clothes?”

Clothes are washed by hostel staff, says Samar. “It is said if a child does all these, when will he study? Then parents search for a hostel that not only provides food but has laundry service too. We don’t have to worry about anything, just study,” says Samar.

“How many hours do you study daily?”

“The first class takes place at 6.30 am. We start studying from then and continue till 2 in the night,” says Samar. He shares his routine with us. There is no time to even breathe in such a tight-packed daily schedule. In between his studies, he just talks twice — once with his parents through a phone and once with the boy who stays in the room next to him.

“If on some day I sleep a little longer, I feel guilty. I feel like crying all the time,” says Samar, who is from Varanasi.

“If you can’t make it to IIT…,” I say slowly, hesitatingly, and leave the question incomplete.

“Haven’t thought about that. But IIT will happen. I am working hard,” says Samar.

Samar avoids direct answers. Just like I find it difficult to ask a straight question.

“If it doesn’t happen!” This thought is that invisible sword hanging on everyone’s head in Kota. Every year many students return home with shattered dreams. Many do not even return.

Most of the coaching institutes in Kota are concentrated at certain areas in the city. Kunhadi, Rajiv Gandhi Nagar, Mahavir Nagar, Vigyan Nagar, Jawahar Nagar are some such areas.

HOSTEL WHERE A STUDENT DIED BY SUICIDE

After meeting Samar, we head towards the area where students recently died by suicide in a hostel and in PG accommodations.

The Boys Hostel looks like a budget hotel in the middle of the market. This is where students who are preparing for medical entrance exams stay. There is a wooden plank over a small in front of the building. As we enter the hostel, the boy at the reception springs up.

“Yes ma’am.”

Two months ago, a student died by suicide in one of the rooms of this hostel. I do not reveal the questions I have as I plan to meet the children of this hostel.

The boy at the reception, who introduces himself as the warden, makes a call in a hushed tone. Then he hands me the phone. A shrill voice from the other end blurts out, “No, ma’am, we can’t allow you to meet the students. Else, you wait till I reach there, then you can meet them.”

“When will you come?”

“It will take time.”

“How much time?”

“Don’t know. It will take time.”

There’s no scope for any negotiation as the call is disconnected from the other end.

From the Boys Hostel I head towards a PG accommodation where a student had died by suicide. The person who runs the place refuses to talk to me.

‘DREAM OF BECOMING AN AUTHOR TORN TO PIECES’

But there are many students who stay nearby.

One of the students says parents get scared when they hear of a suicide from Kota. Then, for several days, they keep calling, multiple times a day, ensuring our well-being. They say “don’t take undue pressure”. After a few days, everything goes back to square one, it’s “back to normal”.

“What does ‘back to normal’ mean?”

“It means they again start talking about studies and numbers,” he says. Coaching institutes take tests every week and the results are shared with parents. “If the score dips even once, they keep asking ‘Is there some issue, son’. You have gone there to study. Your parents want you to do well, that’s why they are spending so much money on you,” he explains.

“I wanted to become an author. I wrote stories but papa tore the copy and threw it away. Mummy stopped talking to me. Now here I am, preparing to become a doctor,” he says.

“Which was your longest story?”

“On relationships. It was 81 pages long.”

“Do you have anything that you have written with you now?”

“No, the copy was torn to shreds, and after that I haven’t written anything.”

I keep digging, refusing to give up. “You must be getting ideas for stories from what you see around you?”

“Yes. Every night, the boy in the room next to mine keeps switching the flashlight of his mobile on and off. And from the adjacent girls’ hostel, the light in one of the rooms switches on and off. Seeing that, I thought of a story but could not write it. I will have to become a doctor only,” he says with a tinge of complaint in his voice. Pain in the eyes on a face that’s beset with a nascent moustache and beard.

There are stories that the 15-year-old aspiring doctor wants to tell, stories that will remain untold forever. Whatever he goes on to become, he most probably won’t become a writer.

A 5-STAR LIKE HOSTEL, NO MEETING IN ROOMS

From there, I make my way to a girls’ hostel. I had informed the hostel management of my visit in advance.

The hostel looks less like a students’ hostel and more like a 5-star hotel. A cursory look at the lounge of the centrally-air-conditioned building is enough to give the feel that an interior designer has put in her best efforts. Huge chandeliers and furniture like in a trendy coffee shop. A reception desk and several framed photos.

There are about 250 girls here, in one of the biggest hostels in Kota’s Landmark City, preparing for medical entrance exams.

I meet the students one by one, in the lounge itself. Going to the rooms is prohibited. “It impinges on their privacy. We don’t even go to the rooms,” says the owner.

There is no conversation with the students. The interaction ends as soon as it begins. “Everything is fine,” is the uniform reply that I get.

I look to fish out the camera from my bag, but a hand touches mine and says, “Please don’t shoot videos, it will be problematic.”

Then I sit on a soft-cushioned sofa with the owner of the hostel, Vinod Gautam. “There are 250 girls in the hostel. We opened the hostel just before the Covid-19 pandemic,” he says. Gautam is talking to me, but is not addressing the most important question.

I don’t beat around the bush and try to bring him to the crucial question. “So many youngsters in Kota are dying by suicide,” I say.

“We don’t have any cases like that in our hostel,” says Gautam.

He then points towards a biometric device and says that parents get to know when a girl steps out.

“If anyone doesn’t return by 7.30 pm, parents are informed. There are nets all around the hostel. Even if anyone tries to jump to their death, the individual will be caught in the nets. The ceiling fans in the rooms have devices attached to them. Any load of more than 10 kg and an alarm goes off,” says Gautam.

There are several e-rickshaws parked in front of the hostel gate. I ask Gautam why they are there.

“The girls take these e-rickshaws to and from coaching classes. Even if they have to go to the market for shopping, they use these e-rickshaws,” he says.

“Everything is very safe here,” he claims.

“Safe how?”

“Even if a girl ventures out at 10 pm she will be brought back in 5 minutes. There are arrangements in place. We have our men in every nook and corner of Kota. Coaching centres too have deployed their people across the city. If a couple is spotted at a tea stall or in a park, they are immediately identified. We then handle the situation in our own way,” says Gautam.

The arrangement that Gautam is branding “safety measures” is visible throughout the city.

Most coaching centres conduct classes for girls and boys separately. If a student is suspected to be going around with someone, they are told that “youngsters have died because of love affairs”. Such students are sifted and sent back immediately. “Why should we sully the whole environment?”

Passing by the hostels, I notice that all the windows are closed, and the doors are shut too. Even if something takes place inside, no one would know for hours. This is what happens most of the time.

A student at a snack stall in Landmark City says, “Every student is given separate rooms so that studies go on smoothly. We only go to enquire after someone when they start missing classes.”

I am reminded of what the police officer said. “Children might come here to build their future, but Kota is a futureless city. Its future is a thing of the past. Now, it is just a repetition of the vicious cycle of competition, loneliness, depression and suicide.”

(This article is the first of a three-part series on Kota coaching institutes and student suicides)